Nathan Nielson: Welcome to The Eclective, a publication and podcast of Books & Bridges, where we explore the wisdoms of the world and apply them to modern life. My name is Nathan Nielson and our guest is Krishnan Venkatesh, professor (or tutor in the parlance of the college), of Eastern and Western classics at St. John's College. Venkatesh is the author of Do You Know Who You Are? Reading the Buddha's Discourses, Frodo's Wound: Why the Lord of the Rings is a Great Book, and a contributor to the forthcoming book on Thoreau as a philosopher. Venkatesh studied English literature at Magdalene College, Cambridge in England. He researched Shakespeare at the University of Muenster in Germany and taught literature and philosophy at Shanxi University in China. Today we examine Henry David Thoreau as an Eastern thinker. Famously difficult to pin to any one school of thought, Thoreau was a proud eclectic who immersed himself in the wisdom literatures of Asian traditions. Venkatesh will expound upon the man who stood apart from the cultural consensus of his time. He fiercely opposed the structures of society and the emptiness of careerism. Thoreau is a perennial voice who paradoxically calls us to closer kinship with the land under our feet and prompts us to seek great souls ranging the global pages of history, philosophy, and science. Krishnan Venkatesh, thank you for being with us.

Krishnan Venkatesh: Thank you for having me, Nathan.

Nathan Nielson: Yeah. So in your current study of Henry David Thoreau, you're in an exploratory phase, you're working on this chapter that contributes to a larger book on Thoreau as a philosopher. How's it been going?

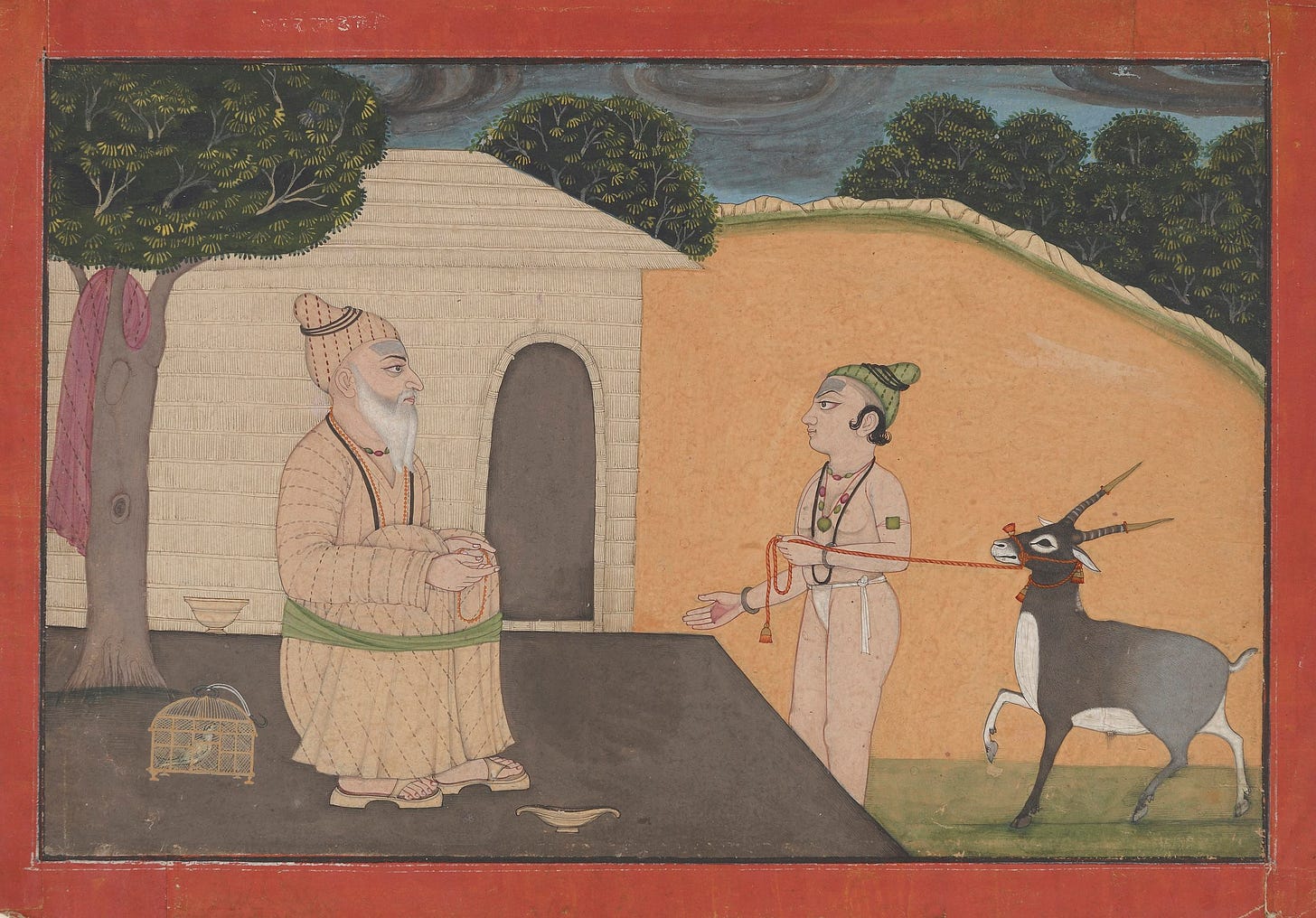

Krishnan Venkatesh: That's right. Well, I will correct one thing you said in the introduction, is that I'm not going to expound on anything because I'm not a Thoreau scholar by any means. But I've been at St. John's for 35 years now and I've been a student of the Eastern and Western classics. So Thoreau is somebody I have not actually read seriously for about over 20 years, I think. So this is a re-visiting of an old hero of mine in light of all the studying I've been doing in recent years, thanks to my editors at Mercer University Press for asking me to take part in this project. So in being asked to write an essay on Thoreau as an Eastern philosopher, I've had to re-think certain things, re-explore this whole area. I mean, so among the things that I've been getting quite excited about, so firstly, I realized, re-reading Walden and A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, that Thoreau was deeply immersed in the Indian texts, you know, in the Vedic literature. He'd read everything that was available in his time in English and French. And it was formidable. But he was also infatuated with Confucius, so you probably noticed that every three pages in Walden he quotes Confucius. So these Eastern texts, these Asian books were very much in the forefront of his mind. He read more Asian books than he read Western books. You know, he was deeply immersed in, he was more immersed in Indian philosophy than in Western philosophy. The Bhagavad Gita was his favorite book. That hit me and I realized that the thinkers around him, Emerson and the other transcendentalists, were also avidly reading all the Asian books that they could get their hands on. And as I looked deeper, I noticed something that I hadn't really thought of before. So let me give you some facts here. Benjamin Franklin was infatuated with Confucius. He wrote on Confucius and he corresponded with Jefferson on Confucius. Jefferson was infatuated with Confucius. He loved Confucius. For both of them, Confucius expressed an ethical standard for the new America. And so the higher elevated ethical standards set by someone like Confucius were calling these men as they were looking for a new way of being, I think, which involves a natural aristocracy, not a born aristocracy, a natural aristocracy. So you have those two. Madison had a portrait of Confucius above his fireplace in his house. And so then I poke even more and I found John Adams was infatuated with the Upanishads. So he was pushing the Upanishads, all his friends. And in fact, he and Jefferson, so the second and the third presidents of the United States had a lengthy correspondence on Eastern great books, especially on the Upanishads. Where John Adams was responding to what he saw as the narrow-mindedness of Joseph Priestley. This is Joseph Priestley, the chemist, the one who came up with the theory of phlogiston. Brilliant man, so wonderfully interesting, quirky character who was also a minister who was interested in comparative religions. And in his book on comparative religions, he attempted to show the superiority of Christianity, and it rubbed Adams the wrong way. So Adams came up with a lengthy screed criticizing priestly for all his failures in understanding the Upanishads. So in other words, these books were at the fabric, the very foundation of this country. So the earliest thinkers, the most formative men in the foundation of this country were thinking through these books. And Adams used, he actually used the word bigotry when he was complaining about Priestley's narrow-mindedness with regard to the Indian traditions. So anyway, so I started thinking that, this is actually pretty interesting. Because if you're trying to understand what an American is or what the American mind is, then you have to confront the fact that in the earliest years of this country, the most formative thinkers of this country, the most central philosophers, I'm thinking the Transcendentalists, Thoreau, they were invoking the East more than anything else. So this was part of the thinking of becoming an American. And I thought this was wonderful and very exciting, in contrast to the extremely narrow-minded white nationalism we see today. So this is where my excitement in this last year originates as I strive to think how to think about this.

Nathan Nielson: Do you think that rich background had an impact in informing America as a pluralistic society? At least planting the seeds for such a society in the future?

Krishnan Venkatesh: Well, surely, so cosmopolitan, embracing a non-exclusive society, a society that had a mind that was interested in everything, you know, interested in the truth, wherever it was. And also, I think these founders were also interested in, and they believed in, the possibility of becoming good people without the Ten Commandments, without the Bible as the framework. So I think it was very important. One of my colleagues, David Townsend, he made a tantalizing remark to me in passing that he didn't think that the United States was a Western nation. And I'm trying to wrap my mind around what that means. And when you think about the respect for individual dignity that this country is based on, and how that expresses itself in an ideal of civil discourse, so about the ideal of respectful civil discourse, even about politics and religion, an ideal that we don't necessarily hold up to today, but that, when you think about that kind of ideal of respect for anybody, you see that it's not in the houses of parliament, British political discourse where people seem to shout each other down and jeer. And so you think, well, where did this come from? The American standard of civil discourse. It’s not in the West, I think, which is very hierarchical. And as far as establishing a society based on respect for the individual, I've heard it said that this is due to Christianity, but no Christian state has ever come up with such a constitution or such an ideal of behavior. So it is something new. So it's something new that's not been seen before. And maybe it's been informed by reading this other stuff and thinking about it.

Nathan Nielson: Yeah, that's really interesting. The founding of the United States of America, the Constitution, and all the founding documents, most people interpret those as kind of the locus of establishing a kind of individualism as opposed to, as you say, inherited aristocracy. But it makes sense that the Asian wisdom traditions would be needed in order to kind of buffer the excesses of individualism that might arise in a kind of democratic system like this.

Krishnan Venkatesh: Yeah, that's very good way putting it, thinking of Confucius in particular and the care for other people that Confucius keeps, Confucius and Mencius keep invoking. Yeah.

Nathan Nielson: And the founding of the United States is at once revolutionary, but it's also very much backward-looking. It does have a conservative type of sensibility in the sense that it modeled its forms of government on the Romans, the Greeks, the Judaic tradition, and so it does have respect for the traditions of the world. I think that kind of breadth is necessary for any kind of republic that hopes to be enduring and lasting. And I think this Asian component just adds to the richness of what we have. Let me just read a passage on page 11 of Walden. Thoreau writes: “The ancient philosophers, Chinese, Hindu, Persian, and Greek, were a class than which none has been poorer in outward riches, none so rich in inward.” And that just makes me wonder, Henry David Thoreau was very much a minimalist when it came to the riches and superfluities of life. What is the connection between wealth and wisdom in Thoreau's mind and maybe as a kind of lesson he learned from Asian traditions – that connection between wealth and wisdom, what do you think?

Krishnan Venkatesh: Yeah. It depends what you call wealth, right? He was not a gatherer of material wealth, that's for sure. And in a way, I think one of the threads that, there are multiple threads that go through, or currents that go through Thoreau's thought. One of them is very familiar to us, the Stoic and Epicurean threads. He was a reader of those philosophies, although I don't think he ever read Marcus Aurelius. But you know, he was a fluent reader of Latin and Greek, as well as French and German. So he was reading this stuff and translating some of it. So you have on one hand, thread number one would be Stoic and Epicurean philosophy that deals with a kind of independence of soul and a notion of happiness that involves simplifying, stripping away extraneous concerns and keeping to the essentials of life, of a human life. So you have that thread going on. Another thread from the classical West is the agrarian literature. Most prominently Virgil's Georgics. So you think all those agrarians. There's Hesiod. And those also informed his work, so the primacy of the farming life, the life of cultivation. And those works are also extremely down to earth. They're anti-urban, anti-imperial in nature. And so there's that in Thoreau, if you can't be happy, a human being can't be happy if he goes too far from the land, from the soil. So there's the aspiration of a kind of groundedness and a kind of attention to the world around you, the world immediately around you, that is in the human scale, right? Not more wealth than you can manage, not more realm than you can manage, it's on the human scale. So there's that, those two threads feed him, I think from very early on. And the man himself, he was not anti-technology. Did you know his family was a family of pencil makers?

Nathan Nielson: I did read that, yeah.

Krishnan Venkatesh: They were master pencil makers and Thoreau was very good with machines and coming up with new inventions. So this was not a Luddite. So this is somebody who worked very carefully with material things, but a pencil, it's a beautiful image, right? It seems so simple, but he came up with a formula for a better pencil lead. And he came up with a way to put the lead into the pencil without cutting the pencil in half. So stuff like that. So he was very engrossed in practical things. He was also the town surveyor. So he was mathematically minded. He was also a voracious reader of natural history writing. So this is the other thread that comes in, is Thoreau the natural historian, who would keep up with Linnaeus. He was inspired by Goethe's natural history writings and Humboldt and then later Darwin. So this other current of Thoreau's thought was natural history writing, Thoreau the natural history writer. And this was something that he, and he was always looking, always studying what was around him and classifying. So when you look at his work, it is prodigious. He could not have done this if his life had not been simplified, right? He didn't have a family, he didn't have any love life to speak of, no emotional entanglements. He had friends, but by and large, it was fairly solitary, with his friends, and without great emotional entanglements. So he lived this life of a Stoic or classical Epicurean, kind of simple and not needing extraneous distractions, which is why he could do so much in such a short time in spite of poor health. But when he reads these Eastern texts, I think one of the things that turns him on is yoga. So he saw himself, one passage in Walden mentions this, as a yogi. And I'm going to quote him: “Simplify, simplify” is from one of his other threads, Rousseau. So he says in the correspondence with his friend Blake, H.G.O. Blake, not William Blake, he says:

“Depend upon it that rude and careless as I am, I would fain practice the yoga faithfully. The yogi absorbed in contemplation contributes in his degree to creation. He breathes the divine perfume. He hears wonderful things. Divine forms traverse him without tearing him and united to the nature which is proper to him. He goes, he acts as animating original matter. To some extent and at rare intervals, even I am a yogi.”

So this kind of thing comes up in his journals also. Let's see. There's another, I believe this is in Walden. So he says:

“Sometimes, in a summer morning, having taken my accustomed bath, I sat in my sunny doorway from sunrise till noon, rapt in a revery, amidst the pines and hickories and sumachs, in undisturbed solitude and stillness, while the birds sing around or flitted noiseless through the house, until by the sun falling in at my west window, or the noise of some traveller's wagon on the distant highway, I was reminded of the lapse of time. I grew in those seasons like corn in the night, and they were far better than any work of the hands would have been. They were not time subtracted from my life, but so much over and above my usual allowance. I realized what the Orientals mean by contemplation and the forsaking of works.”

So this life at Walden is like his attempt to practice being a yogi as he understood it. So he read those works, the Indian shastras, avidly. And one of the things he translated, he worked on this for a while but he translated it later in his life, was the, apart from the Harivamsa, the Meditations of the Seven Brahmans, I think it's called. And he's more interested in the yoga philosophy. So there's a part of him that is fascinated by this and sees his life as being very similar. Now, having said that, I don't think, and having been reading the Upanishads all my life, I don't think that his thinking resembles the Indian Upanishadic thought at all, except with certain images. And one of them is his preoccupation with the dawn. He loves the dawn. And so this thing about the dawn and getting up, bathing in the morning and sitting and contemplating in the morning. That very much is very Indian. You think about the yogis or people meditating at dawn. But his preoccupation with dawn also goes with the Confucian strain. So the idea of an ethical awakening – wake up, wake up. Wake up to a higher being, wake up to a better self, wake up to a more essential self. So these pervade his isolation at Walden. Although at Walden he got a lot of visitors.

Nathan Nielson: How do you understand his relationship between mind and matter? Are they integrated, is one subsidiary to the other? Do they rely on each other? Are they equally balanced? In his experience at Walden Pond, he very much was in solitude and mastered his environment as much as he needed to, but yet he kind of leaned back into meditation. How are those two related in his mind?

Krishnan Venkatesh: That's a great question. I don't think his idea of meditation was something that was separated from nature. It was not as if he was going into some higher realm that was not of nature. So one of the books that he was reading was the Sankhya Karika, the Tattva Kaumudi, which is, and the Sankhya philosophy, as you know, is a dualistic philosophy of nature and spirit in that philosophy we are essentially spirit. We find ourselves born into nature and incorrectly identify with nature. And all our sufferings come from that incorrect identification. But as we grow to spiritual truth, we realize that we are not nature. And so then we separate in our consciousness from nature and end up being pure spirit contemplating nature. So one might say that that philosophy is a philosophy of a separation of consciousness from nature where the contemplative aim is to make a break and say, I am not that and to stand apart looking on until we can see the whole of nature doing its own thing and not feel anything about it. And that's not that dissimilar from, say, some forms of Stoicism where you're freed. It's an idea of liberation. I don't think Thoreau's was like that. I don't think he ever espoused a dualistic philosophy, which is why he was always so interested in the nitty gritty of nature. You he was always measuring. So he was very much a 19th century scientist measuring, doing experiments. His conception of his life at Walden was an experiment. He described it as an experiment. So he's trying things out. He's always measuring, always seeing what grew with what, how it grew exactly, not in vague general terms. So he actually had the mindset of a natural historian. This was not a world, this natural world, is not a world that you're trying to emancipate yourself from. It's a world you're trying to find your correct relationship to.

Nathan Nielson: So that's very anti-Baconian, anti-Francis Bacon, the idea of nature as an object to throw on the rack and torture its secrets out of it. He didn't believe in that, right?

Krishnan Venkatesh: No, not all. He believes in watching things in their native habitat. There's a wonderful passage in The Maine Woods where he takes part in the deer hunting, sorry, a moose hunting expedition. And when the moose is killed and eaten, he feels intensely sad at that. And there's then, let's see if I can find the passage. Give me a second. This is in the Ktaadn section. No it's not, it's in the Chesuncook section. There he laments the tendency of human beings when they see nature to immediately view it as an object for their use. So they see a tree and they see lumber, or they see a moose and they see food. And he has got this wonderful passage. This is in the second section of The Maine Woods, the Chesuncook section where he says:

“Is it the lumberman, then, who is the friend and lover of the pine, stands nearest to it, and understands its nature best? Is it the tanner who has barked it, or he who has boxed it for turpentine, whom posterity will fable to have been changed into a pine at last? No! no! it is the poet; he it is who makes the truest use of the pine, — who does not fondle it with an axe, nor tickle it with a saw, nor stroke it with a plane, — who knows whether its heart is false without cutting into it, — who has not bought the stumpage of the township on which it stands. All the pines shudder and heave a sigh when that man steps on the forest floor. No, it is the poet, who loves them as his own shadow in the air, and lets them stand. I have been into the lumber-yard, and the carpenter's shop, and the tannery, and the lampblack-factory, and the turpentine clearing; but when at length I saw the tops of the pines waving and reflecting the light at a distance high over all the rest of the forest, I realized that the former were not the highest use of the pine. It is not their bones or hide or tallow that I love most. It is the living spirit of the tree, not its spirit of turpentine, with which I sympathize, and which heals my cuts. It is as immortal as I am, and perchance will go to as high a heaven, there to tower above me still.”

So this is Thoreau the romantic speaking when he, it's a kind of contemplative faculty, but it's a contemplative faculty that in a way takes part in the life of every natural being as something with its own autonomy and not a contemplative faculty that in a way stands above it, stands with it. So I can see that the pine is like me, so there's that respect for the pine. And so if it's that kind of contemplation, then it's not really yogic in the Sankhya sense of identifying with pure spirit and breaking away from the ground. This is a way of attaining harmony or relationship, true relationship, with what is around you.

Nathan Nielson: Yeah, that's very interesting. It's a beautiful passage. In that sense, I think Thoreau does differ a bit from his contemporary and his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson, who was probably the leading transcendentalist, who had a tendency to look at nature as a symbol from which to derive some kind of spiritual edification. Whereas I think Thoreau is more, he looks at nature and all of its diversity as kind of independent spheres, independent subjects.

Krishnan Venkatesh: Yeah, yeah, yeah, I think that's right. When he goes up Mt. Ktaadn there's this wonderful passage where he sees just how indifferent nature is to man, that we have no place there, we have no place in certain parts of nature, so it's a caution, as it were, to notice our limits and to hold back. So all of nature is not the extension of my mind, which I think for Thoreau would have been arrogant. I think this is why he spent so much of his time in later years in natural history, in the study of natural history, because he's interested in nature as “other,” in nature as itself and it's not me. There's this wonderful thing about him, is that as I'm reading him, I think that there are passages in Walden that remind me a lot of the Taoist philosopher Zhuangzi, whom he didn't read, whom I don't think he could have read. So Zhuangzi has passages, for example, the story of a tree. So somebody says, what do I do with this tree? Here's this tree that is all gnarled and thorny and the wood is too hard and we can't make it into anything. And Zhuangzi says, why does use have anything to do with the tree? You know, just let it be and admire its amazing life. This tree in Zhuangzi becomes a shrine. Zhuangzi says, why not just lie under its shade? In Zhuangzi it becomes this very, I think, primal and important therapeutic lesson of not trying to assimilate the entire world into your agenda. There's a kind of liberation for yourself in being able to let things be. And you think about that yourself whenever you consider this good-for-nothing relative or family member that you're annoyed with because he doesn't, he’s of no use to you, no use to anyone. But Thoreau is like that a lot. And it goes with the task of simplification in not just having no extraneous suppositions, no extraneous demands on nature, but trying to see it for what it is and letting it be, which I think is important. So he couldn't have read the Zhuangzi. And yet I think that Thoreau’s closest Eastern thinkers, the ones that he was most like, are people he could not have read. So Zhuangzi was one. The other two that come immediately to mind when I'm reading his works are the 12th century Japanese writer Kamo No Chomei, who wrote a small book called Record of a Ten Foot Square Hut. And Chomei was a courtier who leaves the town, leaves the city, goes up into the mountains and builds himself a ten foot square hut that he then lives in. And this is his account. So then you have the Japanese counterpart of Walden. But in addition, there are all those haiku poets, like Basho, who walk. So like Thoreau, they walk. They believe in real walking. They walk into inhospitable places. Their writings are a mixture of poetry, narrative, and reflection. So Basho's Narrow Road to the Deep North, I think, is the Eastern work that is most like Thoreau. But he could not have possibly read those. So if I'm reading Basho and Thoreau's simultaneous essay, these two are brothers.

Nathan Nielson: Reading Thoreau, sometimes you get a sense there's a mystic strain in his writing relating to how different souls or different minds can come to some kind of understanding even though they're not located physically next to each other. There's this kind mystical passage about communication between beings on different planets and different continents. It's interesting how Thoreau absorbs and imbibes these kinds of lessons from writers he never read, but yet there's still some connection. That's kind of mystical.

Krishnan Venkatesh: Yeah, there's something universal going on here, which I think is what the founding fathers were reaching for. A universalist society is what they were seeking.

Nathan Nielson: Now that you mention society, I was just thinking we should talk about Thoreau's views of society and how society can both maybe educate and expand a person's mind but also constrict and limit and burden the free spirit of a human being. What are his thoughts about that? The struggle for social status, the struggle for economic well-being in a very competitive society. It's very, very evident.

Krishnan Venkatesh: Yeah, I think he just thinks it's a waste of time. So you're wasting your time. You're taking yourself away from what you essentially want. It's got nothing to do with happiness. That's evident. It's got nothing to do with peace. So I think he's exactly with the Stoics and with the Epicureans and that it seems obvious to him that in the economy of a human life, that is a waste. And I think he thinks very economically about this. How much time you spend doing something in order to get something that you could have gotten with less time. Or something that even you already have. That story in Walden about the guy who asked him to take the train from this one town to the other and Thoreau calculates in the cost of the ticket. So if you have to work a day to get the train ticket and then you jump on the train it takes you a bit more than a day to get from this town to the other town but if I just start walking today it'll take me half a day to get there. So I think he makes an argument about this, it's not just a posture, it's not just a romantic posture or something grand. But he makes an argument of an economic nature that you are wasting your time in doing these things.

Nathan Nielson: I think one of Thoreau's most famous passages, and perhaps his most famous, relates to not only wasting time, but it relates to the misery that comes from the rat race of a competitive society. He says: “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.” That just strikes almost any modern ear with the ring of truth. Would that also strike, you think, an Asian ear with the ring of truth?

Krishnan Venkatesh: I think so. Let me read you, this is a passage from Zhuangzi:

“Our encounters lead to entanglements and the daily striving of mind against other minds. Hesitations, deep difficulties, reservations and small apprehensions cause restless distress and anguish and produce interminable fears. Like arrows from a bow, we pronounce what is right and wrong. We insist on our views as if they were a covenant. Like the decline in autumn and winter, the failing of our mind is shown day to day. Like water, once emptied, the mind cannot be gathered up again [the mind or the heart in Chinese]. Then the mind approaches death and cannot be renewed to brightness. So let us stop, let us stop.”

And so this sense of waste, we will waste our energies doing irrelevant things, things that are irrelevant to what we really want. So it's there in the Chinese, it's there in Taoism. We dwindle away, we diminish ourselves by doing this. And it's there in all the Indians, this notion that suffering is at the heart of human life. And we wouldn't have any interest in anything spiritual if everything were hunky dory. We listen because we're having a hard time.

Nathan Nielson: So that passage was Zhuangzi that you just read?

Krishnan Venkatesh: Yeah, Zhuangzi in chapter 2.

Nathan Nielson: That was particularly beautiful, I thought. And it's very, for Zhuangzi, seems like it's very straightforward and philosophical instead of metaphorical, what he said there.

Krishnan Venkatesh: Yeah, yeah, it's not metaphorical for sure.

Nathan Nielson: Yeah. Let me read you what Thoreau said in Walden: “Superfluous wealth can buy superfluities only. Money is not required to buy one necessary of the soul.”

Krishnan Venkatesh: Yeah. Beautiful statement. Yeah. And he's obviously looking back at the sages – Socrates Confucius, Jesus, all those sages who had nothing, just the clothes they wore, a hard chair to sit on, that's it. Maybe not even a chair. So I think he's thinking hard about economy, that we fritter our lives away, running around.

Nathan Nielson: Do you think he mostly lived up to his ideals?

Krishnan Venkatesh: Yeah, I do, I do. As I said, he was a pencil maker. So he wasn't a hermit in his hut. And he had a family and he was a filial son. So this is the side of Confucius that I think he lived up to. He was a good family member. And I think he was a good friend, and he had friends. He believed in friendship. In this respect he was very ancient – friendship more important than romance. One way in which one might think that he was acquisitive is that he did have a lot of books. At least he was acquisitive about books. I don't think he had tons of money to go and buy them. Late in his life, he met an Englishman, Cholmondeley, who went back to London and sent him a case of the newest translations of Indian books, a gift that Thoreau treasured, they were beautifully bound, and Thoreau built for it, a boxed chest to hold these books. So he had things, it wasn't as if he was an ascetic in the Indian sense. He had things, he had a life of the mind that one might say was antithetical to a yogi. So a true yogi would pare down the life of the mind to just what was needed for meditation, for the practice. One example of Thoreau's difference from the East was that he lived in his hut at Walden for two years. Kamo No Chomei lived in his ten foot square hut for 30 years. So there's a difference in commitment. So with Thoreau, it was an experiment. And so there's a way in which Thoreau was an inquirer. When we say compared to an Eastern sage, his mind was restless. He was interested in stuff. He would devour the newest natural history book that came out, and read it with scrupulous attention. So one might say that intellectually, compared to a yogi, he was a hoarder. So he had a vast property, fluent in at least four languages, and vast natural history detail in his head that he carried on his head, vast reading, voracious reading, and the ability to wander in these inner worlds that were huge. So he might not have had a lot of land, but he had vast inner lands for himself. He had worlds inside himself. That was unyogic. This is the Westerner who travels. Even Basho, when he walks, it's not with a purpose to gather inner wealth. It's with a purpose to pare down, to face the essential.

Nathan Nielson: Yeah, that's exactly what he said about the inner riches of the philosophers of the ages – outer poverty, inner riches. And I'm also fascinated by this relationship between solitude and friendship. I think one needs the other, for him. Well, in closing, I just want to ask one last question: How is Thoreau relevant to the problems and challenges of today? I mean, you could write a book on that alone.

Krishnan Venkatesh: I think the call to get rid of extraneous preoccupations is the permanent one. So any human being is born into society and born into a situation where expectations are imposed on you and you try to live up to these expectations, you waste a lot of energy, trying to live up to these things that don't make you happy, even perhaps don't make anyone happy. And so I think reading Thoreau is a readjustment of that kind. But that's not different from say a Stoic or Buddhist. The one important thing for me about Thoreau as I read his later works is his idea of the wild. So this partly intersects with his contribution to the environmental movement, in that the reason it's important to preserve wild areas in our country is because access to the wild, externally, is the safeguard to a certain human sanity. And the wild, when he speaks of it, he really means some expense of the soul that is beyond domestication. And that is where you really live. That is where your vitality comes from. That is where your mental health comes from. And I think for him, reading not just Walden, but his later books, Cape Cod and The Maine Woods, this reminder that you need the wild. You need to keep touch with the wild in yourself, some part of you that is irreducibly you, that is you, that you have your own demands, your own yearnings, your own connections, how you see things, everything that's your own, that's what you try to get in touch with. And that's what you try to preserve because that's where you really live. Not in what everyone else thinks you should be doing. And I think all his works, he's a very salutary reminder of that. And hence, he's therapeutic, but I think when one listens to that, everything he says about the wild, and also then what it consequently makes you do, namely pay attention to the stuff that's going on around you, the light and the wind and the leaves and the trees, then you start to live in a new place. Your world becomes new to you and you live more honestly, and I think with greater vitality and greater care.

Nathan Nielson: Wow, those are amazing lessons for us to learn, because our modern life is slowly gobbling up the wild realm, the undiscovered frontier. And also, you mentioned the need for training our attention, getting rid of extraneous matters that make us unhappy. And I think, like you say, Thoreau is almost a prophet of our time, for our time, I think.

Krishnan Venkatesh: For our time, yeah.

Nathan Nielson: So you are going to continue your exploration of Henry David Thoreau, and we would like to talk with you again about what else you find later on. In a few months we'll check back in with you.

Krishnan Venkatesh: Yeah, by then I will have read all his journals.

Nathan Nielson: Wow, that's a feat.

Krishnan Venkatesh: Yeah, reputedly his greatest book. Yeah.

Nathan Nielson: Well, we look forward to hearing more. We'll continue this conversation. But for now, this has been extremely illuminating and deepening. So I appreciate your sharing your time with us. Krishnan Venkatesh, thank you very much.

Krishnan Venkatesh: Well, thank you very much.

Nathan Nielson: Goodbye, see you next time.

Krishnan Venkatesh: Bye bye.

Share this post